When I was 16, I went to Alaska with my aunt and uncle and two female cousins. I rode in a motor home with all the comforts of domesticity. I was the same age Sacajawea was when she served as an interpreter for Lewis and Clark on their Corps of Discovery Expedition. She was either pregnant or lugging a small child through uncharted territories from the Missouri River to the Pacific Ocean. My path led me from Long Island, NY to Alaska, in the middle of the summer. We may have spent five days traversing the unpaved Alaska-Canada Highway, but nobody erected a statue in my honor. Sacajawea had her likeness chiseled time and time again along the Lewis and Clark trail.

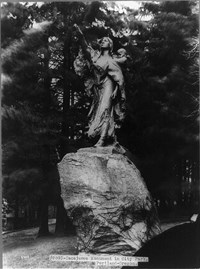

The first and only statue I found of her in 1971 was located in Washington Park in Portland, Oregon. This bronze statue was roughly 8 ft, tall and had been dubbed “The Madonna of the Trail.” It’s easy to see why: Sacajawea is holding her son Jean Baptiste Charbonneau who accompanied her on the trial. Funded by The Women’s Suffrage Association, the statue was created by Alice Cooper and unveiled in 1905. Etched are these words: “Erected by the women of the United Sates in the memory of the only woman in the Lewis & Clark expedition, and in honor of the pioneer mother of Oregon.” It’s not an impressive statue as far as statues go, but the words are an eternal message of hope and praise. Sacajawea acted as a Shoshone interpreter, and despite her youth, inexperience and foray into motherhood, her tenacity and bravery were well-respected. Many people saw her as a beacon of peace. One of her favorite sayings, “Everything I do is for my people,” is still uttered in many indigenous circles.

There are more statues of Sacajawea than any other woman in the USA. Don’t get me wrong, she’s amazing and deserves the bronze treatment. There have been a few recent additions erected along the landscape of America, many of which are glorious, especially the one in the Cascade Locks Marine Park and another one in Three Forks, Montana. But don’t take this the wrong way. Surely, there have been other incredible women in recent years worthy of a bronze bath. I’d be happy with copper, marble or even glass.

Care to nominate someone? Let’s dot the world with monuments of the matriarchy!